By Irma Windy Astuti

May 2nd every year is acknowledged by Indonesians as the National Education Day. This annual commemoration is always associated with its main figure, Ki Hajar Dewantara. One of Indonesia’s national heroes and its first education minister, Ki Hajar Dewantara with his educational philosophy and teachings has fundamentally shaped Indonesian education and we have continued to see their relevance even today, in this 21st century. Besides his famous leadership trilogy in education: Ing Ngarso Sung Tulodo, Ing Madyo Mangun Karso and Tut Wuri Handayani, Ki Hajar Dewantara is also well-known for his Tri Nga (Ngerti, Ngrasa, Nglakoni) and Tri-N (niteni, niroke, nambahi) among his other educational (Tamansiswa) praxes.

This article intends to reflect upon Ki Hajar Dewantara’s Tri Nga: Ngerti (to understand/ comprehend), Ngrasa (to feel), Nglakoni (to do) within the eminent framework of Second Language Acquisition (input, interaction and output hypotheses). To begin with, it is not very clear whether Ki Hajar would take and adopt this educational praxis from the domains of learning proposed by Bloom and Krathwohl which they had developed and published between 1956-1972 (Hoque, 2017). However, long before his passing in 1959, Ki Hajar Dewantara who was born in 1889 has conveyed and advised various merit of teachings during his lifespan. Hence, by the same token, we can say that Ki Hajar Dewantara’s Tri Nga: Ngerti (to understand/ comprehend), Ngrasa (to feel/ to make meaning out of something) and Nglakoni (to do) is Bloom and Krathwohl’s domains of learning which comprises the thinking (cognitive domain), affective domain (attitudes) and psychomotor domain (skills). In general, scholars and educators would agree that all learning can be categorized, understood and inspected through these domains of learning. The learning of a second/foreign language is not in itself an exception.

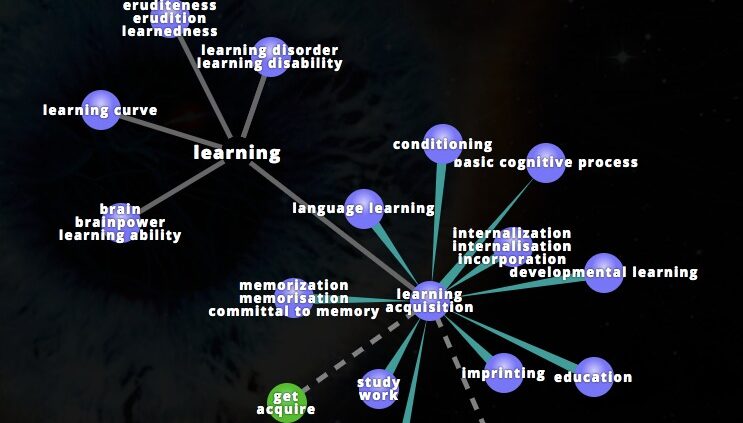

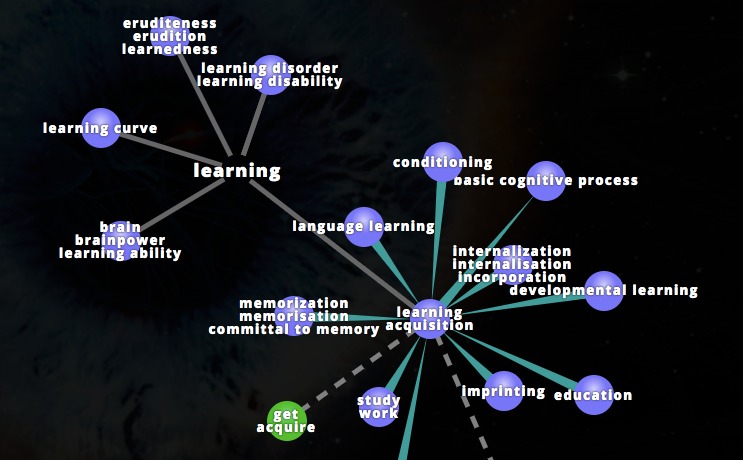

The famous hypotheses related to second language acquisition available thus far, are: input, output and interaction hypotheses, proposed respectively by renowned scholars in SLA field: Stephen Krashen, Merrill Swain and Michael H. Long. From their first inception, the three hypotheses have undergone many scholarly scrutinies and (along the way) got revisited, modified and updated by their immediate theorists and proponents. Clearly, the input, output and interaction hypotheses remain the hallmark of Second Language Acquisition theories which continue to shape L2 learning across the globe. At the heart of those three hypotheses is incontestably the three domains of learning at work in which the acquisition of any second language is the direct result of interplay between cognitive process (ngerti), affective activities/ strategies (ngrasa) and skill building through practice (nglakoni).

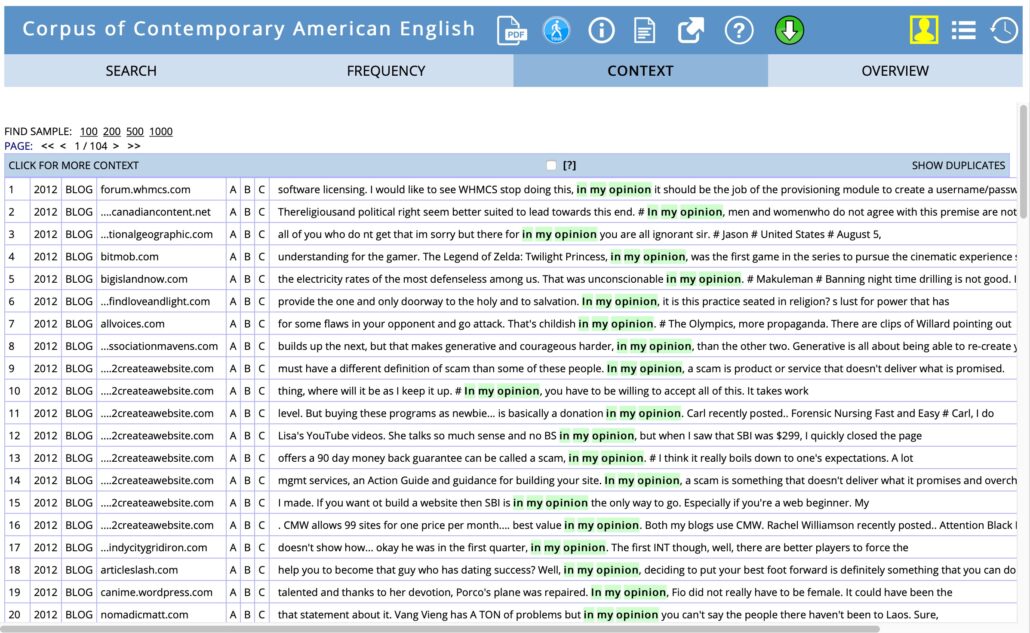

To understand or ngerti is the primary requirement for all learning to occur. One cannot be said to have learned or understood something if she/ he has not fully or partially understood the new information that she/ he is trying to learn or acquire. In other words, when one is deprived of sufficient amount of comprehensible or comprehended input, then learning can be obstructed. The role of input is both fundamental and a precondition to L2 acquisition. Krashen’s input hypothesis (1981, 1985) basically wants to ensure L2 learners that they need to have ample exposure and access to the target language in a form of comprehensible input to acquire the language.

Better yet, many subsequent studies and L2 scholars are also content, as it was claimed by Swain (1985), that the ability to understand a (comprehensible) message in the target language is not the only way to successfully acquire the new language. Other internal and external factors beyond the amount and quality of the language input might also become important determining factors. Other than socio-cultural factors, affective factors have also been verified to define the success level of L2 acquisition. Carrio-pastor and Mestre’s finding (2014) for example, suggests that both integrative and instrumental motivation correlate with successful second language acquisition experienced by L2 learners. Put differently, those having more positive learning outlook, higher self-efficacy and more confidence in learning are generally and instinctively considered as more successful L2 learners. Ngrasa as a mental process and emotional state belonging to affective domain/ conative aspect of learning is equally acknowledged by Ki Hajar Dewantara as one of the essential learning conditions.

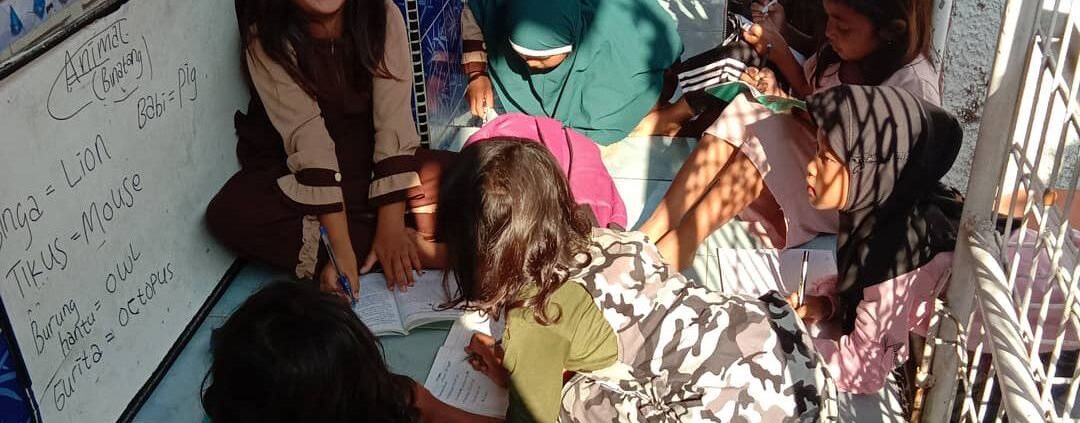

The latter domain, psychomotor learning or in the word of Ki Hajar Dewantara, Nglakoni, is part and parcel of a successful learning journey. Learners’ intent and commitment for the skill development through physical (oral and written) practices that involve mental activity and information processing would not only support another domains – affective and cognitive, but also solidify the acquired skill. In the context of L2 acquisition, this psychomotor learning is signified by the interface of input/ interaction for the basis of language development (Gass,1997). Meanwhile, the output or productive use of language is also a necessary phase which serves as a means of noticing/ triggering functions, hypothesis-testing function, feedback and the metalinguistic/ reflective function (Swain, 1985; Gass,1997). To put it another way, practicing the use of second language in a consistent way through conversational exchanges or interaction with other interlocutors would help improve learner’s fluency and proficiency.

The input, interaction and output hypotheses in L2 acquisition will remain the central theories informing L2 learning and research. In reality, according to Gass & Mackey (2007), the three constructs along with feedback are also non-distinct and interlinked in some ways. Similarly, learning a second/ foreign language would require and involve cognitive activity (ngerti), affective strategies (ngrasa) and psychomotor domain (nglakoni) in which each domain is built upon the others and interact in a reciprocal manner. Understanding the roles and interaction of those hypotheses and domains of learning seems less complicated in the words of Ki Hajar Dewantara. This respected scholar went on to say (in Javanese) that “Ngelmu tanpa laku kothong”, “laku tanpa ngelmu cupet” which means knowledge without action is meaningless and action without knowledge (wisdom) is pointless. Perhaps now, we can get ourselves better reminded of our commitment to learn a second/ foreign language by reflecting on Ki Hajar Dewantara’s teachings and wisdom. Happy National Education Day!

References

Carrio-Pastor, M.L., & Mestre, Eva. M. (2014). Motivation in second language acquisition. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 240-244. https://core.ac.uk/reader/82526160

Gass, S. (1997). Input, interaction, and the second language learner. 3(1). https://tesl-ej.org/~teslejor/ej09/r14.html

Gass, S. M., & Mackey, A. (2007). Input, interaction, and output in second language acquisition. In B. VanPatten and J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction, pp. 175-199.

Hoque, Enamul. (2017). Three domains of learning: Cognitive, affective and psychomotor. The Journal of EFL Education and Research, 2(2), 45-52. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330811334_Three_Domains_of_Learning_Cognitive_Affective_and_Psychomotor

Marihandono, Djoko. (Ed). (2017). Ki Hajar Dewantara: Pemikiran dan Perjuangannya. Museum Kebangkitan Nasional Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Kementrian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

Swain, M. (n.d.). The output hypothesis: Its history and its future [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://www.celea.org.cn/2007/keynote/ppt/Merrill%20Swain.pdf

Yee, C.K.C., Ning, C.S.K., & Hua, S.L.J. (n.d.). Chapter 14- The interaction hypothesis: Why you shouldn’t learn languages alone [Blog post]. https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/hss-second-language-acquisition/wiki/chapter-14/

Photo by the Author

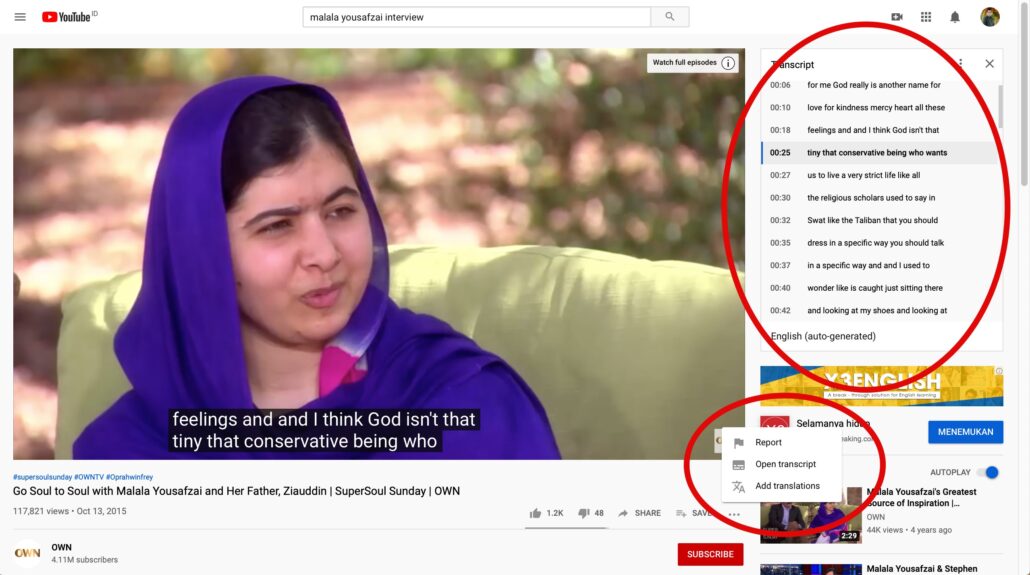

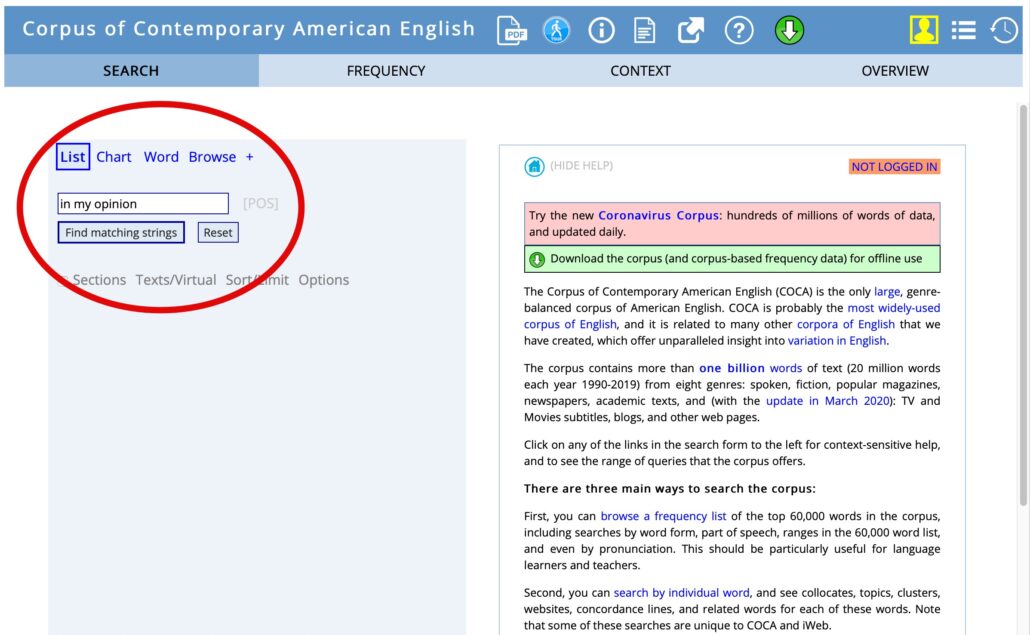

Photo by the Author Photo by the Author

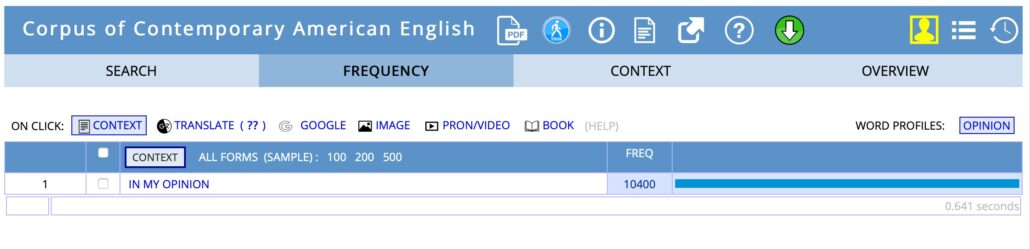

Photo by the Author